My family owns a store that sells dishes, mugs, and fine porcelain, and my uncle recently hired a 2000 lbs bull as our shift manager.

“The price was right,” my uncle said.

The bull cannot operate the cash register. He cannot do inventory. He cannot, honestly, understand how the store works at all. He can’t do anything but destroy things. So that’s what he does, he destroys things. Because he has no other skills.

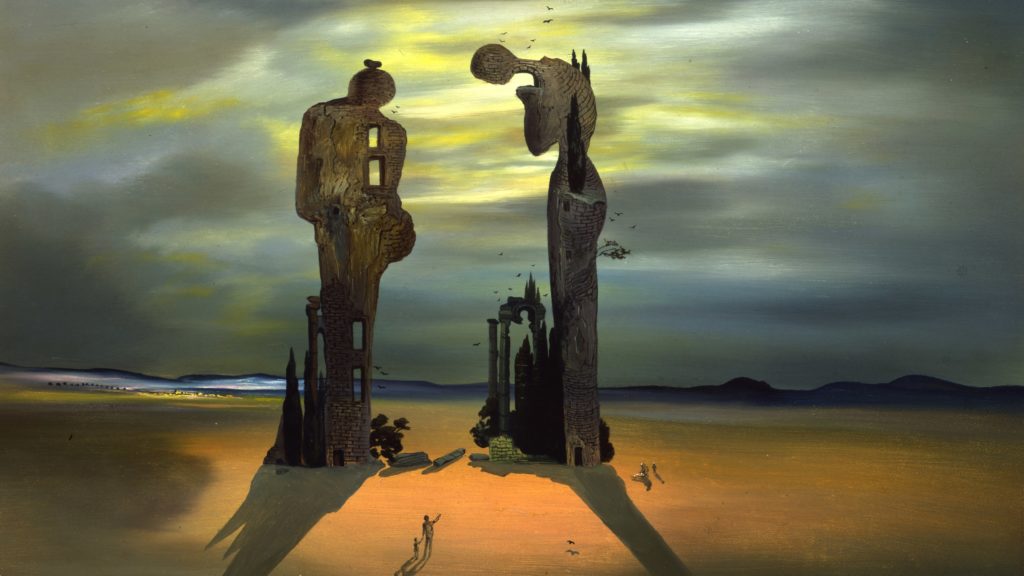

The bull can destroy all the inventory. He can destroy the shelves. He can grunt and look at the computer, and when he cannot figure out how to login nor what the computer is used for, he can smash it.

But no matter how much he destroys, no matter how many employees and customers he stomps, he will never own the store. He can punch holes in all the walls, he can break all the glass in the storefront, but he will never be on the title of the store. This is not his store, no matter how he acts.

All he can do is smash what he doesn’t understand, all he can do is stomp the register because it scares him.

He will do long-lasting harm to our store, and the walls will carry the scars when our children inherit the store, and when our grandchildren inherit the store after them. But he will never own this store. It has never been his.

My uncle should never have hired him. My Tio will no longer be welcome at Thanksgiving.

But the store did not change ownership when the bull was hired. It has always been ours, it is the patrimony that my parents and grandparents built for us.

The bull is destroying the shelves now. And long after the bull has been sold to Far Eastern buyers to be turned into cheap leather handbags, my grandchildren will still be finding glass that will need to be cleaned before someone else gets hurt. But it is still our store.

It is hard to imagine how to remove this bull, how to rebuild the store, how to rebuild the neighborhood. But whether we can imagine how we are going to remove the bull or not, it will be removed. No matter if we can imagine how how the store will be rebuilt or not, it will be rebuilt And it will still be our store, paid for by my grandparents and parents with their sweat and cash and blood and bile and brains.

No matter how much the bull destroys, he can never own the store. Even if he destroys it, he can never have the title.

My family came to this country with nothing, and even if the store is reduced to rubble, we will rebuild the store we own with that same nothing. We’ve done it before, we will do it again. Do we want to rebuild from nothing? No. We would prefer that the last generation to start from scratch was one from the past, but that is not the hand we have been dealt.

It will not be the store my grandparents made, it will not be the same walls, or floor; those are being destroyed by the bull as we speak.

The store will be different, and it will be up to us whether it will be better, more fair, more just. And it will be up to us, and our children and grandchildren, to fight the bulls before they can enter the store again.

Olé.